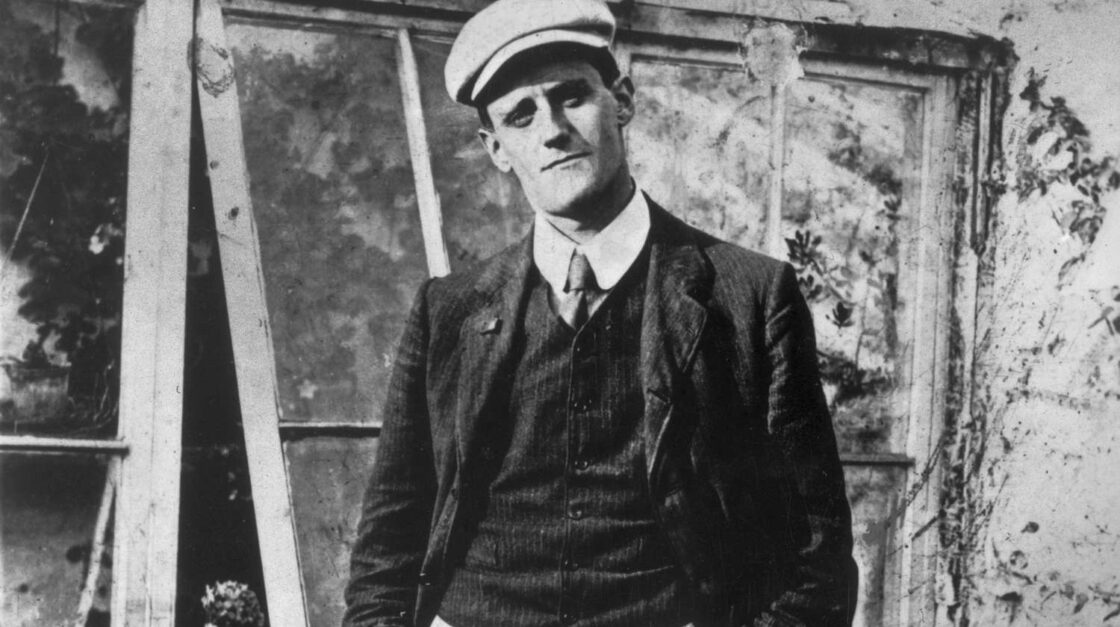

Close Study: A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man by James Joyce

Because this novel is in the public domain, you can find the full text at Gutenberg here.

I finished Joyce’s autobiographical novel A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man earlier this year. When I told people I was reading it, the typical response was, “but isn’t Joyce impossible to read?” Yes, but I went to college for line breaks and metaphors, so it’s too late to question my decision making skills.

Portrait is Joyce’s first novel, and certainly his easiest to read. Nonetheless, it employs a lot of experiments in prose style, particularly stream-of-consciousness. When you learn how to read Joyce’s prose, you get swept up in the beauty of each word he uses, which feels so tightly curated and expresses something essential about the experience of life.

All writers, especially fiction writers, can learn a lot simply by reading and studying his work. I’ll point out a few things that I enjoyed myself:

- The novel’s evolving experiments in prose.

- How extreme moments of beauty can be glimpsed within monotony.

- The relationship between word choice and experience itself.

Portrait had a rather long history to publication. Joyce spent 3 years writing the novel as a 63-chapter work, before abandoning the project and rethinking his approach to the story itself. He set out to tell his story in a realist style, but refashioned the work into a 5-chapter Künstlerroman that makes use of stream-of-consciousness and free indirect discourse—both of which illuminate the psyche of his protagonist, Stephen Dedalus, as he comes to discover his calling as an artist.

To briefly define some terms:

- Stream-of-consciousness: a prose technique in which a character’s thoughts and experiences are transcribed uninterrupted and as they actually occur.

- Free indirect discourse: another prose technique in which a third-person character’s thoughts and actions are written with the intimacy of first-person narration.

- Künstlerroman: a coming-of-age story specific to artists.

The novel was eventually serialized by T. S. Eliot before it was finally published a a book in 1916, 12 years after Joyce began the project. In between conception and publication were plenty of setbacks, including Joyce’s attempt to burn the manuscript in 1911, and plenty of publishers who found Joyce’s experiments in prose difficult to contend with.

And what of those experiments? Joyce sought to transcribe his protagonist’s experiences of reality as they actually occurred. Moreover, those experiences are contextualized in Stephen’s age and place. Take the novel’s opening passage:

Once upon a time and a very good time it was there was a moocow coming down along the road and this moocow that was coming down along the road met a nicens little boy named baby tuckoo….

His father told him that story: his father looked at him through a glass: he had a hairy face.

He was baby tuckoo. The moocow came down the road where Betty Byrne lived: she sold lemon platt.

O, the wild rose blossoms

On the little green place.

He sang that song. That was his song.

On a first read, this passage is a bit bewildering (it certainly was for me). What is going on here? It takes a few more pages of reading, but then you get it—the prose is written in the context of baby Stephen’s experiences. The language is simple but scattered, with word choice that is occasionally infantile, and scattered memories stitched into that thin pleasant blanket we call childhood.

Equally beguiling is when the scene changes without warning. Here’s an example, also from the first chapter, which starts in Stephen’s boarding school dormitory:

All the dark was cold and strange. There were pale strange faces there, great eyes like carriagelamps. They were the ghosts of murderers, the figures of marshals who had received their deathwound on battlefields far away over the sea. What did they wish to say that their faces were so strange?

Visit, we beseech Thee, O Lord, this habitation and drive away from it all…

Going home for the holidays! That would be lovely: the fellows had told him. Getting up on the cars in the early wintry morning outside the door of the castle. The cars were rolling on the gravel. Cheers for the rector!

Hurray! Hurray! Hurray!

The cars drove past the chapel and all caps were raised. They drove merrily along the country roads. The drivers pointed with their whips to Bodenstown. The fellows cheered. They passed the farmhouse of the Jolly Farmer. Cheer after cheer after cheer. Through Clane they drove, cheering and cheered. The peasant women stood at the halfdoors, the men stood here and there. The lovely smell there was in the wintry air: the smell of Clane: rain and wintry air and turf smouldering and corduroy.

What’s happening? Are we still in the dormitory, or is it really winter break now? No—it is simply a dream playing in Stephen’s mind, which we know because suddenly the other dormitory boys start leaving their beds in the morning. This is stream-of-consciousness at play, and it can be beguiling at first, but once you understand these decisions are being made in the text, it gets easier to understand over time.

Joyce’s prose style evolves as Stephen matures. By the time he’s in college, the novel feels much more erudite, with references to scholars and abstract ideas and philosophical questions, as well as dialogue in Latin (a big “thank you” to footnote translations).

As Stephen matures, he stumbles into several epiphanies that guide him towards who he wants to be as an artist. This is another quality of Joyce’s writing: the sudden epiphanies that emerge in everyday life. In Chapter 4, Stephen is in quiet search of beauty, of his motivation to be an artist. At the end of the chapter, we get this excerpt (emphasis mine):

A girl stood before him in midstream, alone and still, gazing out to sea. She seemed like one whom magic had changed into the likeness of a strange and beautiful seabird. Her long slender bare legs were delicate as a crane’s and pure save where an emerald trail of seaweed had fashioned itself as a sign upon the flesh. Her thighs, fuller and softhued as ivory, were bared almost to the hips, where the white fringes of her drawers were like feathering of soft white down. Her slateblue skirts were kilted boldly about her waist and dovetailed behind her. Her bosom was as a bird’s, soft and slight, slight and soft as the breast of some darkplumaged dove. But her long fair hair was girlish: and girlish, and touched with the wonder of mortal beauty, her face.

She was alone and still, gazing out to sea; and when she felt his presence and the worship of his eyes her eyes turned to him in quiet sufferance of his gaze, without shame or wantonness. Long, long she suffered his gaze and then quietly withdrew her eyes from his and bent them towards the stream, gently stirring the water with her foot hither and thither. The first faint noise of gently moving water broke the silence, low and faint and whispering, faint as the bells of sleep; hither and thither, hither and thither; and a faint flame trembled on her cheek.

—Heavenly God! cried Stephen’s soul, in an outburst of profane joy.

He turned away from her suddenly and set off across the strand. His cheeks were aflame; his body was aglow; his limbs were trembling. On and on and on and on he strode, far out over the sands, singing wildly to the sea, crying to greet the advent of the life that had cried to him.

Her image had passed into his soul for ever and no word had broken the holy silence of his ecstasy. Her eyes had called him and his soul had leaped at the call. To live, to err, to fall, to triumph, to recreate life out of life! A wild angel had appeared to him, the angel of mortal youth and beauty, an envoy from the fair courts of life, to throw open before him in an instant of ecstasy the gates of all the ways of error and glory. On and on and on and on!

In Chapter 5, Stephen labors over philosophies of aesthetic beauty, motivated in part by this epiphanic moment. Of course, there is beauty to be found in most of Joyce’s sentences. Here are some of my favorites:

- He pressed his face against the pane of the window and gazed out into the darkening street. Forms passed this way and that through the dull light. And that was life.

- He wanted to cry quietly but not for himself: for the words, so beautiful and sad, like music.

- He was alone. He was unheeded, happy and near to the wild heart of life.

- He heard the choir of voices in the kitchen echoed and multiplied through an endless reverberation of the choirs of endless generations of children: and heard in all the echoes an echo also of the recurring note of weariness and pain. All seemed weary of life even before entering upon it.

In each of these sentences, a strange tension pulls the reader forward, oscillating between mundanity and beauty, and finding a thousand quiet epiphanies along the way.

Finally, what are some things that we can learn from this as fiction writers? Here are a few thoughts:

- It is inevitable that we insert our own selves and personalities into our writing. Some novelists try to resist this, but they shouldn’t, as it’s our own uniqueness that makes our stories valuable.

- Prose style can accomplish valuable work in a story. By controlling the mood, pacing, tone, and musicality of language, we can convey to our readers exactly what we want them to feel without ever stating the emotion.

- Writing should be an act of discovery. If you already know the message of your work, your writing will fall flat. Allow yourself to experiment, to be surprised, and to have epiphanies.

For more on the topic of prose style, check out our article: What is Style in Writing?

Craft Perspective: “Twisting My Life Into a Story Sacrificed My Ability to Live It” by Jessica L Pavia

Read it here, in Electric Lit.

In this lovely essay about orchids and autobiography, Pavia gets into the psychology of writing one’s life on the page. What happens when we turn our narratives into literature, whether memoir or fiction? What are the challenges? How can we do this successfully?

Pavia identifies a mindset that any writer will recognize intimately if they’ve been at their craft for a while:

I’ve already begun to recognize this pattern in myself. Where my decision-making process for attending an event, confronting old friends—really anything—has been reduced to asking myself: “Would I be able to write about this?” Often, it feels like lying. Like falsifying the impulse behind memoir and art. My end goal has switched from gaining a deeper understanding of myself and the world around me to calculating how much I can produce, publish, craft.

This is a feeling I know all too well. Since I’ve decided to call myself a professional writer, I’ve found the need to mine my life, my experiences, and perhaps even others’ experiences for stories. How can I turn this into a poem? Where does it belong in a novel? What meaning can I extract from this simple event, and how can I amplify that meaning for readers?

I’ve been writing long enough now to know that this habit isn’t useful. When I look for meaning in something, particularly before I’ve even written it, I end up inventing something that isn’t true to life or surprising in any way. Perhaps this constant search for stories comes from our culture’s incessant need for more content, more literature, more work; perhaps I’m also trying to validate myself as a professional writer, because the more publication credits I have, the more confidently I can say that this is my calling.

As further evidence that this isn’t a healthy writing habit, Pavia writes it best:

My first essays were purer. I didn’t know what they were going to become as I wrote them: the decaying deer carcass I found in the woods; the extra pigmentation that made itself at home on my face; my need for validation that morphed into inappropriate bonds with English teachers. I lived my experiences as they happened, and only later twisted them into something charged. Those stories feel more real and palpable than anything I’ve since forced into existence. They have heart and complexity, overlapping themes and invisible threads that I later wrangled apart and put back together again. That doesn’t happen when you decide what a story will become before it happens.

This mental habit doesn’t produce good work. Acknowledging that is easy; unlearning it is much harder. Pavia asks an important question: “What if I stopped fabricating intention and metaphor where there is neither?”

I think Joyce did this successfully. He might fabricate, as all good storytellers do, and his metaphors and images can come off as dramatic, overly-heightened. Even so, they’re true to his experiences. The writing is high when his feelings are high; existential when his questions are existential; childish when the protagonist is literally a child. Whether your writing is autobiographical or entirely distinct from your life, an experience can be just an experience; a doorway into new work; a question, not an answer.

Here are some other thoughts on the topic:

- Writing Autobiographical Fiction

- Fiction vs. Nonfiction

- Experimenting in Fiction

- On Living the Questions (an article for poets, but certainly relevant to these topics within fiction writing)

I read Portrait in high school, and after a few readings, I was delighted in his inventions. He captured poetic imagery in storytelling. I even bought a set of CD’s in Ireland of an audiobook performance of it and it was great. My life was enriched by Joyce’s works and it is very pleasing to look into his later works.

Sean, thank you for this work on Joyce and craft and more. I drilled down at every opportunity and came away with an education that outstripped anything my literary criticism courses in grad school provided. Nice work.

Gratefully yours,

Karen

Thank you for the kind words, Karen!

Best,

Sean