This article is all about concise writing, summed up in the timeless phrase “Omit needless words.” We’ll examine some of the best advice on writing concisely, define what concise writing is and isn’t, and describe 11 writing habits that encourage concision.

“Omit Needless Words” and The Elements of Style

In 1920, William Strunk Jr. published The Elements of Style. This was a groundbreaking work for writers, as it was the first English style guide—emphasizing, among other things, the importance of concise writing.

Since then, Strunk’s style guide has been adapted and edited several times; in 1959, E. B. White doubled the book’s length with his own advice.

The Elements of Style has this to say about concision:

Omit needless words.

Vigorous writing is concise. A sentence should contain no unnecessary words, a paragraph no unnecessary sentences, for the same reason that a drawing should have no unnecessary lines and a machine no unnecessary parts. This requires not that the writer make all his sentences short, or that he avoid all detail and treat his subject only in outline, but that every word tell.

In the 21st century, this advice still rings true as a concise (see, they’re doing it!) definition of concise writing.

What Concise Writing Is

Concise writing is writing that has trimmed excess.

Concise writing is writing that has trimmed excess. It is writing that practices the prescription to “omit needless words.”

The key phrase here is “needless words.” These are words that muddy your writing: they distract the reader from central ideas, fail to carry their weight in meaning or impact, or cloud the reader’s picture of the world you are building. Even if you can’t point to these needless words, you’ll know they’re there, because they make writing feel loopy, slack, and unpolished.

Concision is not about writing in a clipped or spare fashion, but simply means that every word carries its weight—whether you’re writing in simple phrases or long lyrical sweeps.

Again, concision is not about writing in a clipped or spare fashion. Concise writing simply means writing that is clear, vivid, and impactful—writing in which every word carries its weight. This is true whether you’re writing in simple phrases or long lyrical sweeps.

The opposite of concise writing is not long writing; it is wasteful writing.

And so the opposite of concise writing is not long writing; it is wasteful writing, writing that fails to display an economy of language.

Omit Needless Words: 11 Elements of Concise Writing

Below are 11 writing habits that will tend to maximize the impact of each word you write. Some are positive patterns to consider adopting. In other cases, it’s easier to understand concise writing when you see what not to do. Learning to identify common mistakes that lead to wasteful writing will help you greatly with writing concisely.

1. Use Concrete Language and Expressive Verbs

The easiest way to write concisely is to use descriptive language. If you can condense an idea into a single word, it often makes more sense to use that word than to overstate it in 10 words. Expressive language goes hand-in-hand with concision.

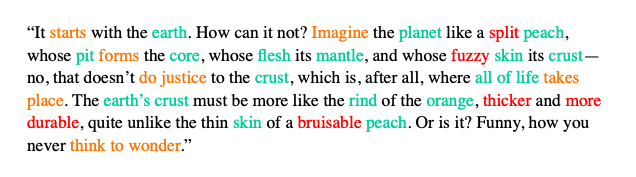

One of my favorite authors, Ruth Ozeki, has mastered expressive language. Let’s look at the opening passage from her novel All Over Creation:

This paragraph is filled with nouns and active verbs, which are the core of expressive language. With a little bit of connective tissue (prepositions, pronouns, articles, etc.), those nouns and verbs combine into a beautiful image of our planet as a peach.

Notice, also, the frequency of each word category. Ozeki uses an equal amount of concrete nouns and verbs; additionally, she occasionally uses adjectives, though only about one-fourth as frequently as nouns and verbs. This expressive language comprises half of the entire passage.

What would a wordy, inexpressive version of the same passage look like? I’ve tried my best to recreate the verbose, unconcise alternative:

In this example, there are far more of those connective words. Further, many of the nouns and verbs are far from expressive: “story,” “corresponding,” and “never-ending violence” are concepts without specific images, and the reader isn’t clear on what the narrator is trying to compare.

When you’re struggling with a sentence, focus on the nouns and verbs; often, you need very little else.

The gist: words can carry a lot of weight, so let them. When you’re struggling with a sentence, focus on the nouns and verbs; often, you need very little else.

This piece of advice largely mirrors our article on great word choice, which has additional concise writing exercises. Take a look there for a further exploration of the parts of speech.

2. Write in the Active Voice

In our previous examples, we only highlighted the active verbs. It’s also possible to write in the passive voice, but doing so is generally less concise.

In an active voice sentence, the subject does the action (the verb). In a passive voice sentence, the verb happens to the subject.

In active voice writing, the subject does the action. In passive voice writing, the action happens to the subject.

Active voice: My wife visited the beach.

Active voice: The rain is drenching us.

Passive voice: The beach was visited by my wife.

Passive voice: We are being drenched by the rain.

Passive voice phrases always use the verb “to be” in some form.

Passive voice phrases always use the verb “to be” in some form:

- Be

- Are

- Is

- Was

- Been

- Were

- Being

Passive voice has a place in writing, but it often adds excess to your sentences. The passive voice waters down your verbs, making them less direct and impactful. Let’s take a quote from The Princess Bride and move it into the passive voice:

Active: Hello. My name is Inigo Montoya. You killed my father. Prepare to die.

Passive: Hello. I am named Inigo Montoya. My father was killed by you. You are encouraged to prepare to die.

Hopefully this gives a sense of passive voice writing: it tends to feel wordy, bureaucratic, impersonal. In active voice writing, the subject takes action. In passive voice writing, action happens to a passive subject, and that makes for alienating reading.

Passive voice writing tends to feel wordy, bureaucratic, impersonal.

As a note, scientific and bureaucratic writing intentionally use the passive voice: writers in these fields want to be speaking impersonally, and so they change phrases like “The government requires your tax payment” to “Your tax payment is required” or “The five of us identified a new protein” to “A new protein was identified.” But this is rarely the goal in more creative and expressive forms of writing.

Don’t swear off passive verbs entirely, just use them sparingly. When you do use the passive voice, use it to offer important descriptive details.

Use passive voice at times to offer important descriptive details, or to describe events outside the subject’s control.

For example, here’s a great use of the passive voice, from the US Declaration of Independence:

The passive voice emphasizes “men” and “equal,” shifting the lens from the Creator to Mankind himself. For its time (1776), this sentiment is rather radical, as it actively called for representative democracy in a world largely ruled by divinely-chosen kings.

You can also use passive voice when something happens outside of the subject’s control. For example, if your character gets hit by a large beach ball, despite being in line in a coffee shop, then the passive voice makes perfect sense.

Here, passive voice properly highlights something happening to a passive subject: being hit by an unexpected beach ball. But concise writing is rarely a series of these kinds of accidents: the character above took other actions, like “turned from the cash register,” that would read very badly in passive voice (“As the cash register was turned away from by him…”).

The bottom line: be careful about the passive voice, as it often creates needless words.

3. Watch for Needless Repetition

A surprising amount of writing repeats itself. Redundancies occur inevitably in writing, but learning to recognize and condense them is a necessary element of concise writing.

Redundant language is language that doesn’t provide new or unique information.

Redundant language is language that doesn’t provide new or unique information. For example, if I started writing about the green grass, that would be rather redundant, since grass—unless otherwise specified—is green. If this greenness is somehow unusual, then perhaps it makes sense to write about, but if the green grass is just a background part of the world I’m building, I don’t need to tell you it’s green—and you don’t need to be told, either.

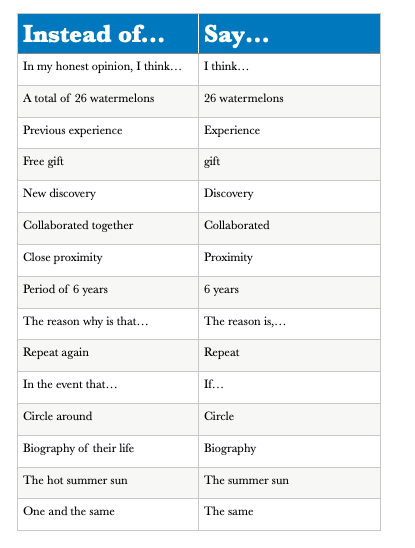

We also let redundancies slip when relying on colloquial turns-of-phrase. A lot of the phrases we use in English are redundant, especially transition statements and verbal colloquialisms. To give you an example, the chart below lists common English phrases on the left, with concise synonyms on the right. You may use these redundant colloquialisms in dialogue, but we recommend almost never using them in poetry or the narration of prose.

After seeing these examples, you may notice how easily redundancies slip past us. We speak many of these phrases without thinking about them; but as writers, we have to start noticing when our words aren’t working. Limiting your use of adjectives, adverbs, and colloquial phrases is a good place to start: each is a hotbed of redundancy, as we’ll discuss.

4. Limit Your Use of Adverbs

I’ve just mentioned a crucial rule for concise writing: limit your adverbs and adjectives. What do I have against these parts of speech? It’s nothing personal, but when writers omit needless words, adverbs are often the first to go.

Adverbs are words which modify verbs or adjectives.

What are adverbs? They are words which modify verbs or adjectives. Adverbs act like adjectives for verbs (and sometimes for adjectives), offering additional information about the way the verbs are performed.

Let’s look at a simple sentence that uses an adverb:

Sentence with adverb: The dog sat lazily on the couch.

Here, the adverb “lazily” modifies the verb “sits.” As the author of this sentence, I have decided that the dog’s laziness is crucial information for the reader.

The English language has a lot of words: we often don’t need to use an adverb because there’s a verb that denotes the same thing.

However, I have also used an extra word to describe that laziness. The English language has a lot of words: we often don’t need to use an adverb because there’s a verb that denotes the same thing. The following adverb-less sentences all convey the same information, in fewer words:

- The dog rested on the couch.

- The dog relaxed on the couch.

- The dog lounged on the couch.

- The dog lazed on the couch.

Each of these examples portray different aspects of laziness, without ever using the word “lazily.”

Adverbs often violate the “Show, don’t tell” rule of writing, as they present excess information instead of inviting the reader to visualize the scene directly. See the following two examples for “Show, don’t tell” alternatives to our initial sentence:

- The dog curled into the couch.

- The dog sighed and sank deeper into the couch cushions.

The issue is not word count; it’s that “lazily” works—well, lazily. It tells your readers what to know rather than inviting them into the world you’re creating, or at least looking for a verb that could carry its weight. It’s a tiny missed opportunity.

Don’t forswear adverbs entirely, in part because “entirely” is an adverb.

Don’t forswear adverbs entirely, in part because “entirely” is an adverb. But the thesaurus is often your friend as a writer, and if a shorter equivalent exists, you should use it most of the time. If you can’t find the right verb, then go ahead and use an adverb: I don’t think there’s a simple English synonym for an activity like “surf ironically.” But for phrases like “destroy completely” (“obliterate,” “annihilate,” or simply “destroy”) or “descend suddenly” (“plummet,” “tumble,” “fall”) you’ve definitely got some options.

5. Don’t Overuse Adjectives

You don’t want an adjective to do a noun’s work.

Overuse of adjectives can also threaten concise writing. You don’t want an adjective to do a noun’s work; if there’s a noun that’s easy to visualize, you don’t need adjectives to modify that noun.

For example, you don’t need to tell us about the color of a fire hydrant—unless that color is notably different.

Unnecessary: They drove past the red fire hydrant.

Most readers, at least in the United States, will assume that the fire hydrant is red.

Better: They drove past the fire hydrant.

Or, necessary again: They drove past the aquamarine fire hydrant.

What an unusual color for a fire hydrant! Perhaps this is a doorway to other, equally discolored objects throughout the city. Perhaps the road paint is green, the stop signs are indigo, and the streetlights shine like spider’s silk in moonlight.

Of course, this doesn’t apply just to colors. Adjectives can be used in any of the following ways:

- Physical traits: furry, soft, lukewarm, etc.

- Emotional traits: happy, excited, suspicious, etc.

- Quantities: three flowers, six moons, two roommates, etc.

- Comparison: the tastier drink, the ugliest house, the hottest day, etc.

Overuse of adjectives leads to a muddy, overemphatic style that can feel like the writer is having readers’ experience for them.

Overuse of adjectives leads to a muddy, overemphatic style that, in extreme cases, feels like the writer is having readers’ experience for them:

Muddy: We savored the cool creamy white-and-red strawberry milkshakes, an almost sinfully delicious relief on a sweltering midsummer July day.

Consider which adjectives really matter for the reader’s own experience:

Better: We enjoyed strawberry milkshakes in the July heat.

Let your nouns do most of the work, and bring in the occasional adjective to help paint a more vivid picture.

Writers need adjectives more frequently than they need adverbs, but don’t overuse them: hopefully fewer than half of your nouns will carry adjectival modifiers. Let your nouns do most of the work, and bring in the occasional adjective to help paint a more vivid picture.

6. One Idea per Sentence

In ye olde days of Classic Literature, writers often wrote sprawling sentences that covered a wide range of images or ideas without pause. Just take a look at the opening sentence of A Tale of Two Cities:

These are classic lines in Western literature, and they work partly because their chaos and jumble nicely mirrors the chaos and jumble of the French Revolution. However, we strongly encourage you not to write this way unless you’ve got an extremely good reason. To juxtapose numerous Big Concepts in a breathless jumble worked for Dickens in this instance, but it’s much less likely to work for modern sensibilities, and even here it makes for confusing and almost overwhelming reading.

The key word is “breathless”: in prose like the above there’s no chance for us, as readers, to collect our thoughts. This is where “one idea per sentence” comes in as good advice.

Let’s take a sentence that says too many things, and see how we might rework it.

The reworked example above takes care not to chain together choppy declarative sentences—which can be one risk of overapplying a “one idea per sentence” style—and manages to convey each core idea with more clarity and focus.

7. Avoid Qualifying Sentences

Qualifying sentences exist to modify another sentence, adding contributing details. They often end up adding needless words.

The wordy example above has a second sentence tacked awkwardly after the first sentence, providing information that the first sentence could provide.

In general, try to limit your use of qualifying sentences. Instead, combine descriptions into single sentences, and omit needless words from there.

8. Don’t Overrely on Auxiliary Words

Auxiliary words are “connective tissue” words. They don’t tell you the main information, but they help provide direction, clarifying the relationship between nouns and verbs. Most sentences require a little bit of connective tissue, but only write auxiliary words when needed; there are many opportunities for you to omit needless words here.

The following are types of auxiliary words:

- Auxiliary verbs: these are verbs which indicate action while also modifying the main verb of a sentence. In English, the main auxiliary verbs are be, do, and have. In the sentence “I can help you,” “can” is the auxiliary verb, because it modifies “help,” the main verb. (“Help” is the main verb because it is the main action. “I can you” isn’t a sentence, but “I help you” is.)

- Prepositions: words that provide direction for verbs. These words indicate how a verb affects a noun. Some prepositions include: for, from, to, in, out, on, off, among, with, without, across, about, above, below, since, under, through.

- Conjunctions: words that connect or separate nouns. The three conjunctions are “and,” “but,” and “or.”

- Determiners: These are words which exist solely to indicate something. Definite determiners include words like “that,” “these,” “who,” and “which.” (“A,” “an,” and “the” are articles, which is the “indirect” form of a determiner. Articles are grammatically necessary; non-articles are often optional.)

- Pronouns: these are words that stand in place for nouns. You should only use pronouns if the noun has already been used, and you should use them primarily for stylistic purposes—to avoid awkward repetitions or to write dialogue, for example. Some pronouns include: he, his, her, hers, they, theirs, who, your, it.

Try to write sentences that are mostly nouns, verbs, and adjectives, and use auxiliary words when they are grammatically necessary or present crucial information.

9. Limit Turns of Phrase

The English language has countless idioms, colloquial expressions, and vernaculars. In other words, turns of phrase—a great opportunity to omit needless words.

A turn of phrase is any sort of expression that the audience won’t understand from context alone. The phrase means something that the words themselves don’t denote, such as the phrase “under the weather,” which means “sick.”

Many figures of speech are both wordy and clichéd, and substitute others’ generalities for your own specifics.

Many figures of speech are both wordy and clichéd. Occasionally, you can work a figure of speech into something tongue-in-cheek, but often, using them in your writing simply substitutes others’ generalities for your own specifics.

Here’s a great list of common idioms to avoid for most English dialects. Turns of phrase simply don’t carry the same weight that concise writing does, so let your words speak for themselves.

10. Limit the Use of Fancy Words

In general, this article advises using fewer words where possible, but this is certainly not an absolute rule. Simple multi-word phrases are often significantly clearer than obscure, esoteric words that say the same thing. Simple writing is more concise—in the sense that the reader can more easily glean meaning—even if it uses more words overall.

Simple writing is more concise, in that the reader can more easily glean meaning.

Although the “smart-sounding” sentence is concise, it’s far from readable. And longer words often carry connotations you may not want: “clandestinely” isn’t actually a great word choice in the first sentence above, because it usually means “secretive in the manner of professional spies” rather than “secretive in the manner of shy high school students.”

Use fancy words sparingly, when they illuminate something that simpler language cannot.

Concision means maximizing what we offer readers for their time and effort. Big words sometimes help with this: if we write “a clandestine meeting” rather than “a meeting conducted in an environment of secrecy,” we’ve helped our readers. But a habit of using big words runs counter to concision. Use “fancy” words sparingly, when they illuminate something that simpler language cannot.

11. Avoid Overstatement

Overstatement is any sort of excessive, superlative description. It’s not just a red car, it’s the reddest car on the road; it’s not just a warm day, but the hottest day imaginable.

Overstatement reduces impact, by diminishing the writer’s legitimacy.

Overstatement aims at maximum impact—but it actually reduces impact, by diminishing the writer’s legitimacy. It’s like someone who bangs the table after everything he says: can we take this person seriously? Is everything that emphatic?

Hyperbole can be an effective literary device. However, you should use superlative descriptions sparingly. The imagery in your writing should do the work for the reader, showing them the red car or hot day rather than telling them that it’s a huge deal.

Are These Concise Writing Tips Universal?

In other words, should you abide by all of these tips, all the time?

should you abide by all of these tips, all the time? Not at all.

Not at all. Writers break the rules all the time, testing the barriers of language and meaning. However, in order for us to break the rules, we must first learn the rules.

And our rule-breaking should be within an overall goal of best using the reader’s time and attention—which is what concise writing and “omit needless words” is all about. That’s not a rule worth breaking.

Omit Needless Words in a Writing Workshop

It’s hard to be objective about our own work, and concise writing requires you to omit needless words ruthlessly. A writing workshop can help. Writing workshops can pinpoint excess words at a line level and help clean up the work’s style—something every writer needs to fix in revision.

An extra set of eyes never hurts when omitting needless words, so take a look at our upcoming courses!

Concise writing will both sharpen and polish your writing style. Put these tips to practice, and watch how your language gains weight, clarity, and power.

Apologies, the correct link is: https://alekshaecky.github.io/concise_writing/

“He was short” etc aren’t examples of the passive voice but standard subject/verb/complement sentences, in this case used as descriptions.

The passive always uses a second verb: subject/be in the correct form/past participle. “He was short-changed” for example.

Otherwise, a useful piece.

Bea (writer and English teacher!)

The Real Person!

The Real Person!

Thank you for pointing that out, Beatrice! I’ve updated that part of the article with better examples. You’re awesome!

You’re welcome (and thanks for the awesome, but I’m just doing my job!)

[…] Concise Writing: How to Omit Needless Words […]

[…] Writers.com College Writing Skills with Readings (Langan & Albright – McGraw-Hill LLC – […]