I’ve been thinking a lot about comedy this summer. We just launched a self-paced course called Writing Funny with the comedy writer Simon Taylor, and his presentation of comedy’s inner workings has made me reflect on my own experience of it.

Comedy (I did standup, improv, and comedy writing when I was younger) has delivered the most raw pleasure I’ve ever experienced. I’ve always wondered why I liked it so much, and I think I’ve come to a clearer answer in the past couple of weeks.

For me, the greatest pleasure of comedy is that it accesses deeper truths directly.

For me, the greatest pleasure of comedy is that it accesses deeper truths directly. What good comedy conveys is so strange, so difficult to speak about (or even notice) under normal circumstances, and yet so deeply true, that the surprise is like me finding a large emerald in my couch cushions. I love comedy for its ability to unearth and share these deeper truths, without the usual restrictions of politeness, convention, and so on: to share how life actually is, without even pretending that it makes the normal kind of sense.

The Deeper Truth

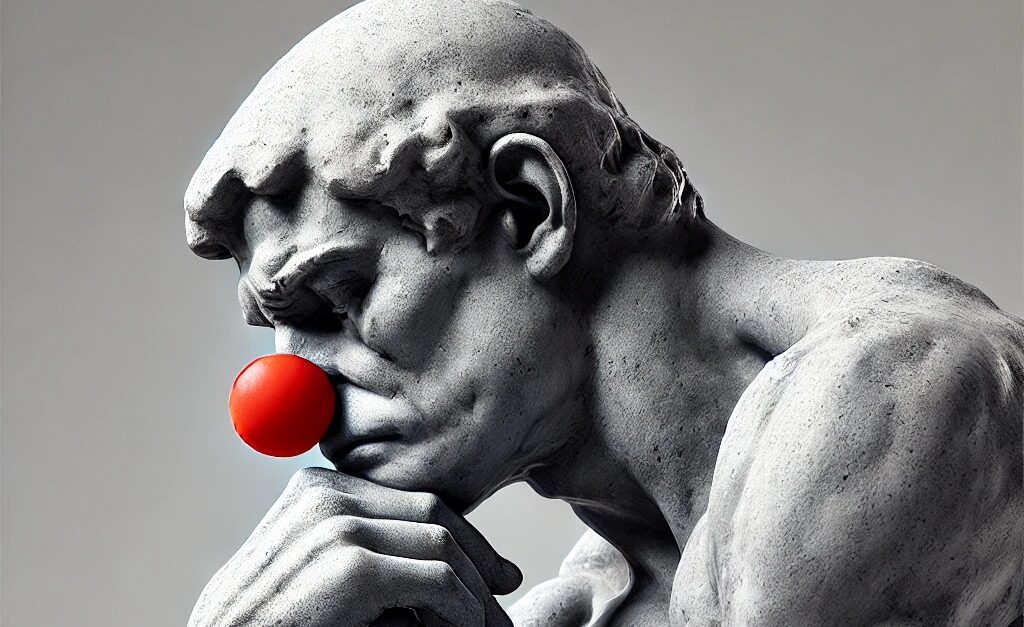

The first piece of comedy that made me reflect in this way was this Instagram post from Simon a few weeks ago:

Since Simon and comedy were on my mind anyway, this made me contemplate the power of comedy itself: I went into my next Zoom meeting laughing sporadically, which meant that I needed to keep turning video on and off (hard to distract someone that much with just a social media post), and I saw that almost 120,000 people liked the post (hard to get 120,000 people to do anything!).

But why did I like it? Obviously, the post progressively intensifies typically masculine traits (physically large, deep voice) into a silly and unexpected final product (a revving racecar with eyes and a mouth). That’s its basic comedic skeleton. But for me, the satisfaction—the meat on the skeleton, what makes the whole experience feel good—is the Deeper Truth the post conveys.

I’d describe that Deeper Truth along these lines: “Many men want to feel more masculine, but the idealized masculinity we envision is almost inhuman, and isn’t especially attractive to us or anyone.”

That’s true! As I have experienced it, the ultimate fulfillment of the drive to be “more masculine” would be to become some sort of unfeeling, invincible murder machine—like Optimus Prime, but possibly without even the weakness of having any close Transformer friends. The NFL used to animate, without humor, exactly this male fantasy:

Another way to discuss this is that Simon’s post wouldn’t be nearly as funny if he turned into a toaster, because it wouldn’t be as true: men feel obliged to turn into big powerful machines like racecars, not domestic little machines like toasters. Noticing the bizarreness of that type of contour is why I love comedy. Men often do want to turn into, like, racecars or fighter jets? or, like, some sort of bipedal tank?—and often, it’s not because we actually want it for ourselves, but because we somehow think we should.

I would ignore this truth presented in a sociology paper or an op-ed; but Simon’s post made me consider all of it, and in an environment where considering it brings pleasure. It points, in such a strange but resonant way, to something about life we barely notice.

Comedy Can Err

Comedy is, of course, not an infallible guide to truth. I’ve been reflecting on the ways my tastes in comedy have changed as I come understand life itself differently.

My favorite piece of my own humor writing is from 2005: “Excerpts from the Script of Toby: The Boy Who Was Raised by Barnacles.” (Here’s the full text.) In each excerpt, Toby, surrounded by made-for-TV-drama trope characters, does barnacle things:

MRS. KEARNSEY: Toby, you’re not eating your dinner.

MR. KEARNSEY: Yes, eat up, Son. Your mother cooked you a nice meal, and it’s getting cold.

(TOBY extends his legs and cirri and begins to sweep for plankton.)

MR. KEARNSEY: (Quietly) Diane, I’m beginning to think this was a mistake.

MRS. KEARNSEY: (With deep resolve) I’m not giving up on him, Harold. I’m never giving up on him.

One wonders: Is Toby a barnacle? Or a very oddly conditioned human boy? This would be clear in the movie itself, but the piece plays with the way text withholds information.

For me, the piece’s Deeper Truth is something like: “Despite all the pomp and circumstance of human life, on some level we are simply animals, carrying out programming etched into us by inscrutable, ultimately meaningless forces.” This is also the theme of Norm MacDonald’s famous “Moth” joke, recorded around the same time (in 2009).

I used to believe this truth—and, in general, the default scientific nihilism I absorbed from my education—far more deeply than I do now. I and other humans are still always acting embarrassingly animal; but I now find that there’s a lot more to life than that, in a way I didn’t when I was 20. Stressing the indignity of our animalness no longer feels essential, like some sort of philosophical cornerstone, and I find that my own piece on the theme feels far less urgently-slash-delightfully true than it used to.

Comedy shines light on things, but it can shine too much light on one thing for too long.

So I feel comedy often goes awry when it overstresses one side of the story, often based on cultural currents. Comedy shines light on things, but it can shine too much light on one thing for too long.

At present, for example, I feel comedy in the US is overdue to stop boosting nihilism. US televised animation traces this clearly: the early seasons of The Simpsons may be the best art (of any kind) produced in the past 50 years. It’s squarely postmodern—reckoning with life’s sudden loss of clearly prescribed meaning—but within a basically warm and caring family and community container. Family Guy copies the format of The Simpsons almost exactly, but throws away the heart in favor of a distilled nihilism; the comedy is effective but nauseating, like Cool Ranch Doritos. Subsequent animated shows targeting the same core audience of young white males (Rick & Morty, Smiling Friends) go progressively further, with, I would argue, diminishing returns. The fashionable attitude that “Existence is a spinning, maddening void, and it’s all anyone can do to not collapse from the despair of it all” has some truth to it—a little—but it just isn’t as true as the amount of screen time it’s getting.

Comedy can also reflect deeper “truths” that are fully lies—as long as those lies are widely believed. A clear example is the vilely racist comedy of 100 years ago. (Coincidentally, I just learned today that the name “Jim Crow” originates with a racist vaudeville show.) The people of the time thought they were really onto something, something that needed saying and repeating. They were deluding themselves, and causing great harm to everyone. Comedy can expose deeper truths, but it can also reflect and reinforce a culture’s blind spots; and it’s painfully difficult to know which is which except in retrospect.

Gentleness in Comedy

I wasn’t in standup comedy long enough to be funny in the way I wanted—that is, in a way that reflected my worldview or values. (Beginning standups will say or do anything to get a laugh, because it’s so difficult.) However, another comedian in Boston, whose name I’ve unfortunately forgotten, showed me a clear glimpse of where I wanted to go. He told a joke about having accidentally called the police over something frivolous. The responding officer said, “While I was wasting time on this, you better hope no one kidnapped your friends and family.” The comic replied, “I always hope that!”

This joke (which killed on stage, by the way) was very memorable to me, because of its unusually gentle spirit. For me, its Deeper Truth is something like: “I am making foolish mistakes in a world full of anger and intensity. I’m not sure what to about that, other than to reiterate my hope that things go okay.” That’s funny! Stumbling through a cosmic knife shop, knocking over the display cases, hoping they don’t slash anyone’s feet and legs: are our well-wishes enough? Should we apologize? To whom?

This joke isn’t premised on humanity being doomed or the whole thing being a lost cause, as contemporary humor tends to be, while also not going the toothless route of ignoring the world’s real problems. If I could’ve gotten good at standup, I would’ve liked to head in this direction.

I find that my five-year-old daughter is an avatar of this kind of comedy. Children are naturally funny, because their minds make a different kind of sense from ours: they assert the altered perspectives that make comedy tick. (This is what it means that they “say the darnedest things.”)

This is my daughter, about a week ago, asking why airplanes go so fast:

Proud parenthood aside, that is effortlessly funny, in a way an adult might never achieve. Picasso said it took him “a lifetime to paint like a child,” and this is like that.

The Deeper Truth I find here is, once again, quite gentle: “It’s odd how time works—how it’s a source of constant pressure, to the point that we feel late even when we turn up in an entirely different city.” That is odd, as well as sad, but being so deep into my adulthood I never would have remembered the oddness of it.

This way of innocently inspecting the deep oddness brings up questions that are quite profound, more so than most adult comedy could do. Why are we so bound up by space and time? Is existence always marked by these limits? They don’t seem native to us—we have to learn them, as my daughter is still doing. Could we ever, somehow, live beyond them?

The Deeper Truth

For me, the pleasure of comedy is the access it affords to the shifting substrate of life: ever out of reach, ever strange, best accessed in thought not tracked by our usual ruts and limitations. I hope this vantage point on comedy is helpful for you. It has been for me: noticing the deeper things comedy says has really brought them to life for me.

Thank you for reading!

Great article.

I’ve no idea if killed on stage means went well or badly. But that’s just me, an English man in York.

Thank you! It means did well. 🙂

Thank you for this article with its profound thoughts. I appreciate what I learned about writing with humor (as well as the performing and other related aspects) most especially about the deeper truths comedy can reveal.

And if I may add this: I am seeing another example of your writing interest in spiritual nonfiction, something which I am also contemplating on pursuing. So thank you, too, for the inspiration to venture further into this genre. May your pen (or keyboard/pad as the case may be) continue to bear more fruitful words!

Thank you so much, Maria! I really appreciate the encouragement.